The Importance of Minnesota’s Bats

Image of a flock of bats flying by Gabriel Ugahayon

They might not be everyone’s favorite creature, but bats are some of nature’s most underrated heroes. Silent, swift, and essential—these little mammals do more good than most people realize.

Although I missed it by a few weeks, I still wanted to write a blog post about bats in honor of Bat Week, which takes place each year from October 24th to 31st. It’s an international celebration that highlights the importance of bats to our ecosystems and raises awareness about their conservation. I encourage you to visit the official Bat Week website to learn more and discover ways you can help support these fascinating creatures!

Image of a Big Brown Bat taken in Utah by the Bureau of Land Management

What are Bats?

Bats, though small and generally harmless, are among the most misunderstood and feared mammals. They belong to the order Chiroptera, a Greek term meaning “hand-wing”—a fitting name considering their unique anatomy. Scientists divide bats into two suborders—Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera—which together include about 180 genera and more than 900 species. After rodents, bats are the second-most-diverse group of mammals, accounting for about 20% of all known species. In some tropical regions, bats even outnumber all other mammals combined!

These nocturnal flyers use echolocation—a biological sonar system that interprets reflected sound waves —to navigate and hunt for food. Their wing structure is equally fascinating: they possess incredibly fine-tuned muscles, including plagiopatagial muscles, which are hair-thin fibers embedded within the wing membrane that allow for precise control during flight. Studies have also shown that bat wings maintain a cooler temperature than their bodies, a discovery that could help scientists better understand how human muscles function in cold conditions.

All in all, bats are truly remarkable little creatures—far more helpful and interesting than their spooky reputation suggests!

Image of huddled bats taken in Cades Cove Loop Road, Tallassee, TN, USA by Jody Confer

Importance of Bats in Minnesota

Minnesota is home to eight different species of bats, each weighing less than an ounce. These tiny mammals play a huge role in keeping our ecosystems healthy. About half of Minnesota’s bat species migrate south each fall in search of warmer weather, while the others tough it out through our harsh winters. Unfortunately, in recent years, bat populations have seen a steep decline. While some of this is due to human activity, a major factor is White-Nose Syndrome (WNS), which is a devastating disease that has spread rapidly among hibernating bats.

Bats benefit our environment in more ways than most people realize. All of Minnesota’s bats are insectivores, meaning their diet consists entirely of insects. On a single night, one bat can eat up to 1,500 mosquito-sized bugs—a natural form of pest control that we can all appreciate during those buggy summer evenings! Beyond helping keep mosquitoes in check, bats also support agriculture by feeding on crop-damaging pests. In fact, experts estimate that bats provide about $3 billion worth of ecosystem services each year in the United States alone.

Image of bats flying taken by the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service

White-Nose Syndrome (WNS)

As I mentioned earlier, White-Nose Syndrome (WNS) has had a devastating impact on many bat species. Before going further, let’s take a closer look at what this disease is, how it spreads, and why it’s so harmful to bats.

White-Nose Syndrome is caused by a fungus called Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which attacks hibernating bats in North America. It was first identified in New York in 2006 and has since spread across most U.S. states and into parts of Canada. The results have been catastrophic, and millions of bats have died. Three of Minnesota’s Bat species in particular—the little brown bat, northern long-eared bat, and tri-colored bat—have suffered population declines of over 90%.

Image of a Little Brown Bat in Greeley Mine displaying White-Nose Syndrome. Taken by Moriarty Marvin, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The disease gets its name from the white fungal growth that appears on infected bats’ noses and wings. Because bats depend heavily on their wings, this damage can be devastating. During hibernation, bats slow their metabolism and lower their body temperature to conserve energy. WNS disrupts this process by waking them prematurely, causing them to burn through their fat reserves far too quickly. Infected bats use twice as much energy as healthy ones, often leading to death by starvation before spring arrives. The fungus can also cause unusual behavior, such as flying during the day or venturing out into the cold when they should be resting.

Bats mainly spread WNS to each other, especially at shared hibernation sites like caves and abandoned mines. However, humans can also spread it by unintentionally carrying fungal spores on clothing, shoes, or gear. If you’re someone who enjoys exploring caves, it’s important to thoroughly clean and decontaminate your equipment to help prevent further spread of this deadly disease.

Our Species

Wintering Species

Image of a Big Brown Bat by John MacGregor

Big Brown Bat (Eptesicus fuscus)

Image of a Little Brown Bat by John MacGregor

Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifungus) or Little Brown Bat

These bats are long-living, with a record 32-year-old bat documented in Wisconsin. Once one of the most common bat species found in MN, they have been heavily affected by WNS. Researchers have seen a >90% decline in wintering Little Brown Bats. During warm months, they roost virtually anywhere. During cold months, they roost exclusively in caves and mines. They have short brown hair with smaller features than Big Brown Bats.

Image of a Tri-colored bat in Russell Cave, AL by the National Park Service

Tri-Colored Bat (Perimyotis subflavus)

These are MN’s smallest bat, weighing only as much as a nickel. Their coloration can distinguish them: the forearms, nose, and ears tend to be pink rather than brown. They have three distinct bands of color on their hair shafts, which give them their names. Little is known about their summer roosting preferences, but they hibernate exclusively in caves and mines, which has made them susceptible to WNS. They are the longest-hibernating bat species in MN, and are often the first ones in the caves and the last ones out. As of 2023, they were listed as federally endangered.

Image of a Northern long-eared bat hanging from a rock by USFWS

Northern Long-Eared Bat (Myotis septentrionalis)

These bats closely resemble the Little Brown Bat, but have much longer ears (as the name implies). These bats are becoming increasingly more rare to see as they have been greatly affected by WNS. In 2022, they were officially listed as federally endangered. Similar to Little Brown Bats, they roost nearly everywhere in the summer, but roost exclusively underground or in caves during winter.

Migrating Species

Image of a technician holding a Silver-Haired Bat in Glacier National Park

Silver-Haired Bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans)

These bats are dark black with pigmented skin and have silver-tipped hair on their backs. They live in forested areas and are only occasionally encountered. Occasionally, they use bat boxes. They migrate to warmer climates in the winter.

Image of an Evening Bat taken by a member of the U.S government

Evening Bat (Nycticeius humeralis)

For most of its documented life, this bat only came as far north as Illinois. However, recent studies have found these bats right here in MN! It’s unknown why this species is beginning to shift its range, but it’s changing nonetheless. They share several traits with Big Brown Bats and are about half the size of Little Brown Bats. They use tree cavities to roost in the summer, and they migrate during the winter months.

Image of a Hoary Bat by Paul Cryan, U.S. Geological Survey

Hoary Bat (Lasiurus cinereus)

These are the largest bat species found in MN, and are known for their distinctive multicolored fur. They have yellow patterns near their faces, and white-frosted tips over everything else. When flying, their wingspans can reach up to 14 inches! They are rarely seen because they roost in tree canopies. During the winter months, they migrate to warmer climates.

Image of an Eastern Red Bat hanging from a tree by the National Park Service

Eastern Red Bat (Lasiurus borealis)

These bats are named for their striking bright red fur. They camouflage into dead leaves incredibly well and are often solitary, which makes them rarely encountered. During the summer months, they are found in heavily forested areas. During the winter months, they migrate to warmer regions, but may briefly migrate under leaf debris.

How to Live with Bats

Image of a Bat Box taken by Mark Buckawicki

Since bats can sometimes carry diseases that are harmful—or even fatal—to humans, it’s best not to let them make their way into your home. Placing bright lights in attics or crawl spaces can help deter them, and it’s equally important to bat-proof your home by sealing off any small gaps or entry points.

If a bat accidentally gets inside, try to let it leave on its own, or carefully capture and release it with proper precautions. However, if you find a bat that appears sick, injured, or unable to fly, do not release it. Instead, contact your county health authorities for guidance on safely submitting it for testing. If you believe you’ve had any direct contact with a bat, it’s essential to visit a local clinic for evaluation. Bats can carry rabies, which is almost always fatal to both humans and animals if untreated. Thoroughly clean the area after removing a bat. Bat droppings can transmit histoplasmosis, a potentially deadly fungal respiratory infection.

To support bat populations while keeping them out of living spaces, consider installing bat boxes. These are artificial roosting structures that provide safe shelter for bats, especially during the summer months. Female bats often gather in these boxes to raise their young, making them an excellent way to encourage healthy bat communities. For guidance on building and placing bat boxes, check out the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources website—they offer detailed plans, design tips, and advice on the best locations to install them in your yard.

Image of a wildlife biologist checking bat caves for WNS on the East Coast. Taken by the Bureau of Land Management, Oregon and Washington.

How Can We Help?

- Prevent the spread of WNS by honoring cave closure guidelines and avoiding caves where bats may be hibernating. It’s also important to decontaminate your gear if you do choose to visit a cave.

- Don’t disturb hibernating bats. Hibernating animals need all the energy they can get, so when you disturb them, you may deplete them of energy.

- Help bats survive by practicing safe bat-removal techniques and never intentionally poisoning them. You can also build them artificial roosts, such as bat boxes.

For more information on White-Nose Syndrome, visit the Response Team Website.

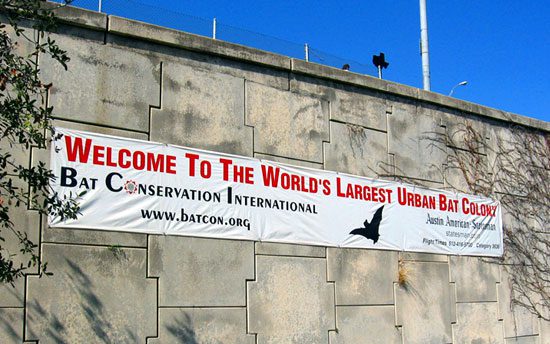

An image showing a banner on the side of South Congress Bridge in Downtown Austin, Texas, where people gather to watch over a million and a half bats take flight.

Minnesota’s bat species may not always get the appreciation they deserve, but their impact on our state is undeniable. From keeping mosquito populations in check to protecting crops and maintaining balance in our ecosystems, these tiny night fliers play a big role in nature’s rhythm. So next time you spot one swooping through the twilight, take a moment to admire it instead of shrinking away. I encourage you to dispel your fear of bats—they do more for our ecosystem than you and I combined!

Here, at Campfire Bay Resort, you can find bats swooping around on warm summer evenings, snatching up those pesky mosquitoes we’re all happy to see disappear.