Migratory Birds: Nature’s Frequent Flyers

Image of Common Cranes flying by Mohamed Fsili

Look up — the sky is on the move! Honking geese, dancing cranes, and speedy little songbirds are all heading south for the season. It’s nature’s biggest commute, and you’ve got a front-row seat.

An Overview of Migration

Imagine a life with warm, sunny winters and no TSA lines to get there. Sounds nice, right? Well, for migratory birds, this dream is a reality — they fly thousands of miles south each year without a boarding pass. But it’s not all smooth sailing: storms, predators, and human-made obstacles like buildings and power lines make these epic journeys risky, turning every migration into a true test of endurance and survival.

If you’ve ever looked up to see V-shaped formations slicing through the sky or heard the melodic flurry of songbirds preparing for a long journey, you know migration season is nothing short of magical. If you’ve ever experienced a Minnesota winter, you’d understand why some migratory birds are willing to travel thousands of miles to get away.

Internal instincts play a large part in aviary migration. Biology is guiding them every step of the way. One of the most phenomenal examples of migration comes from the Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisea). These birds breed in the Arctic and spend winters in Antarctica. They travel nearly 50,000 km every year, and can make the trip over 20 times during their lifetimes. Now that’s a pretty extreme example, but even birds that reside in Minnesota can travel upwards of 20,000-30,000 km per year. Too bad these birds can’t rack up frequent flyer miles!

Image of a globe by Adolfo Félix

Why Birds Migrate

For centuries, the mechanisms behind migration were foreign to researchers. Such long migrations entail increased mortality risks. Bad weather, sea crossings, and so much more can pose dangers to migratory birds. More importantly, traveling that far has a large energetic cost. Nearly 10,000 species of birds migrate every year. Many, if not all, of them face difficult navigation problems. Even the slightest changes in magnetic forces can throw them off their tracks. So why don’t they just stay home?

Bird migration isn’t just a whimsical adventure; it’s a survival strategy honed over millennia. It relies on many different factors such as temperature, daylight, and food scarcity. During winter, insects vanish, berries are buried underneath frost, and open water for ducks and geese freezes over. These changes mean life or death to birds. Birds respond to these environmental cues with instinctive urgency, flying hundreds or even thousands of miles to warmer regions where resources are abundant.

To better understand migratory birds, we must look at the distances they travel:

- Permanent residents, do not migrate. They can find food sources year-round. An example of a Minnesota species is the American Cardinal.

- Short-distance migrants make relatively small movements. Typically, from higher to lower elevations. An example of a Minnesota species is the Red-winged Blackbird.

- Medium-distance migrants cover distances that span hundreds of miles. An example of a Minnesota species is the Sandhill Crane.

- Long-distance migrants typically move large distances, sometimes covering thousands of miles. An example of a Minnesota species is the Osprey.

Image of European Starlings migrating by Sean Foster

Evolutionary Reasons Behind Migration

Many species are finely tuned to changes in daylight, known as photoperiods, which trigger hormonal shifts that prepare them for migration. Fat storage, restlessness (or “zugunruhe,” a German term meaning migratory restlessness), and navigational instincts all kick in, ensuring they’re ready for the journey ahead. Some even use the Earth’s magnetic field, the position of the sun and stars, and familiar landmarks to chart their course. Nature’s GPS, if you will.

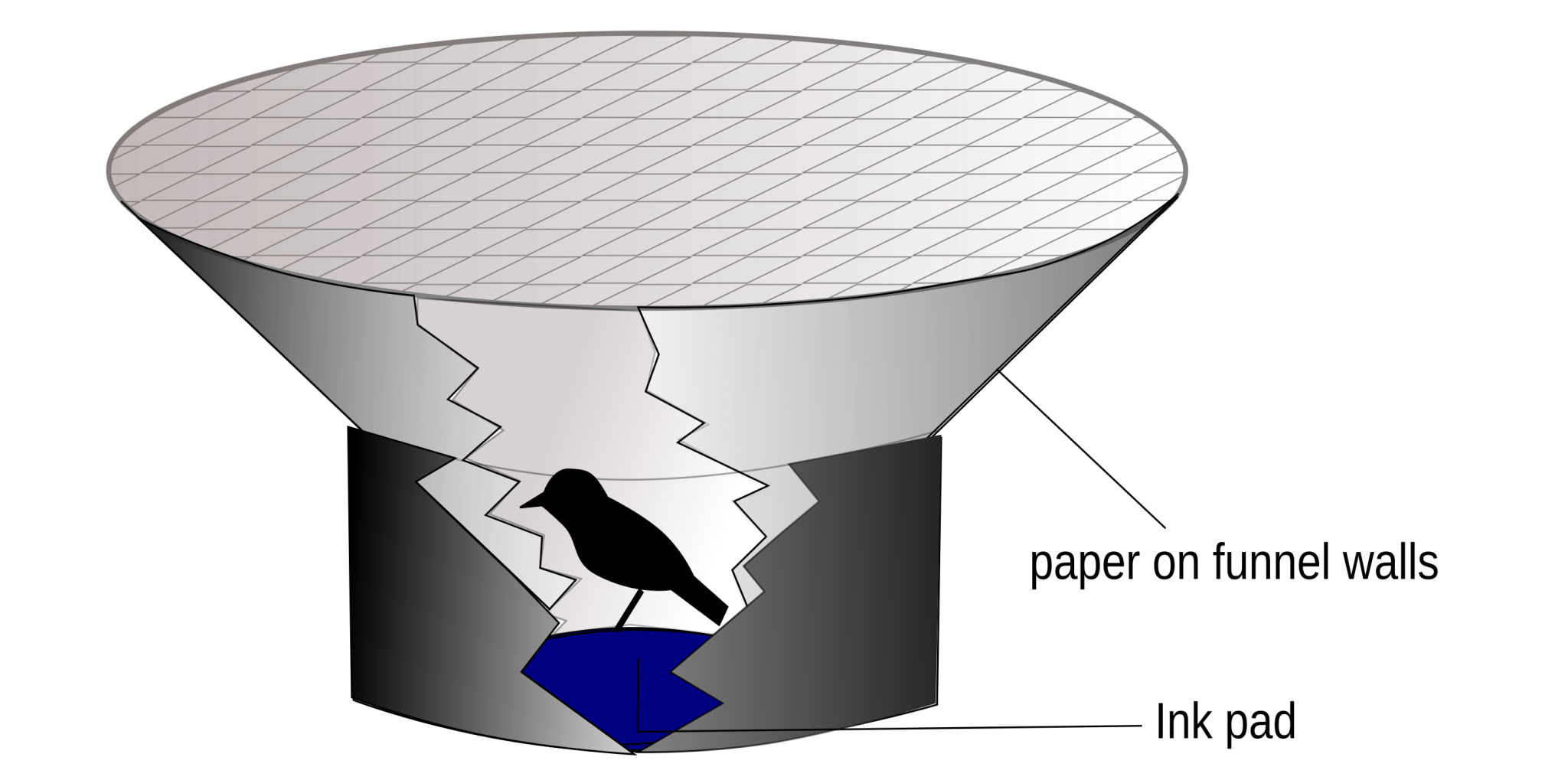

Emlen Funnel Experiment

The Emlen Funnel experiment, which was developed in the 1960s by Stephen T. Emlen and J.T. Emlen, used ink and birds in cages to measure migratory restlessness. Using a planetarium, Emlen was able to manipulate the patterns of the stars that were visible to Indigo Buntings. Tracking the ink patterns that the birds left, he noted that they continuously oriented themselves based on the rotation of the stars. When he artificially changed the ‘north star’, the birds adjusted their directional alignment accordingly. Later research also proved that birds use the Earth’s magnetic field for orientation.

Illustration depicting the Emlen Funnel Experiment by L. Shyamal. A bird is in a cage shaped as an inverted cone, with an ink pad at the bottom. As the bird attempts to fly in a specific direction, it slides down the side and leaves an ink trail on the paper.

Why Don’t They All Leave?

Not all species of birds are migratory. Even through harsh winters, many Minnesota birds stay in the Northern Hemisphere. Chickadees, cardinals, and many woodpecker species tough it out for the long months of winter. These species can stay because they’ve adapted to focus their diets on things that are available during our cold season. Black-capped chickadees, for example, are incredible with memorization, and they often store food in hundreds of different locations to make it through winter. Many permanent resident bird species have also adapted to fluff out their feathers to create better insulation when it starts getting cold.

The genetic makeup of every species and subspecies of bird is different. These evolutionary codes determine whether or not migration will occur, and how far it might take them.

Image of Black-Capped Chickadee on a branch full of snow by Amanda Frank

Who’s on the Move?

Geese

If you hear honking overhead, it’s probably geese. Canada geese are the iconic V-formation flyers, conserving energy by riding the updrafts created by the bird in front. Snow geese, with their bright white plumage and black-tipped wings, also migrate through Minnesota, creating spectacular clouds of birds that can number in the tens of thousands. Peak viewing: late September through early November. Watch in the mornings or late afternoons, especially near lakes and open fields, where they stop to rest and feed.

Cranes

Sandhill cranes are the ballet dancers of the sky — graceful, high-stepping birds with haunting calls that echo across wetlands. They often gather in large “roosting” flocks before heading south. Peak viewing: mid-September to mid-October. The Mississippi Flyway is a hotspot, especially in prairie wetlands and river valleys.

Hawks and Raptors

Autumn skies are also filled with raptors, riding thermals as they head south. Broad-winged hawks, sharp-shinned hawks, and red-tailed hawks form large flocks called “kettles,” often numbering in the hundreds. Look for them near ridgelines and open fields on sunny days, when thermals provide lift. Peak viewing: late September through October.

Ducks and Waterfowl

Minnesota’s lakes and rivers attract a variety of ducks during migration. Mallards, teal, northern pintails, and canvasbacks stop over to rest and feed. Diving ducks, like the redhead and scaup, make dramatic splashes as they settle on open water. Peak viewing: September through November, especially near large lakes, river mouths, and shallow wetlands.

Songbirds

These smaller travelers often go unnoticed until a morning chorus hints at their passing. Orioles, warblers, sparrows, thrushes, and many other species typically migrate at night. Peak viewing: late August through early October. Binoculars and patience are your best friends here, as they pause at berry-laden trees and shrubs along their route.

Shorebirds

Minnesota’s wetlands and mudflats host sandpipers, plovers, and dowitchers during migration. These long-legged, fast-moving birds are often found probing mud for insects and crustaceans. Peak viewing: mid-August through September, particularly in shallow wetlands and along riverbanks.

Why Should We Care?

Humans have always been fascinated by this natural phenomenon. Birds themselves have played an important part in human storytelling and traditions. In almost all cultures, flocks of birds mark the transition into winter and later on mark the arrival of spring.

Migration is more than a visual spectacle; it’s a reminder of nature’s delicate balance. Birds help control insect populations, pollinate plants, and disperse seeds — all while maintaining ecosystems that humans rely on. By observing migration, we connect with a rhythm that has existed long before cities and highways, a cycle that reminds us how interconnected life truly is.

Migration also serves as an early warning system for environmental change. Shifts in timing, population numbers, or routes can indicate broader issues like climate change, habitat loss, or pollution. By observing and supporting migratory birds, we become stewards of the land and water they depend on — and, by extension, the environments that sustain us.

Image of migratory birds flying by Arthur Tseng

How We Can Help

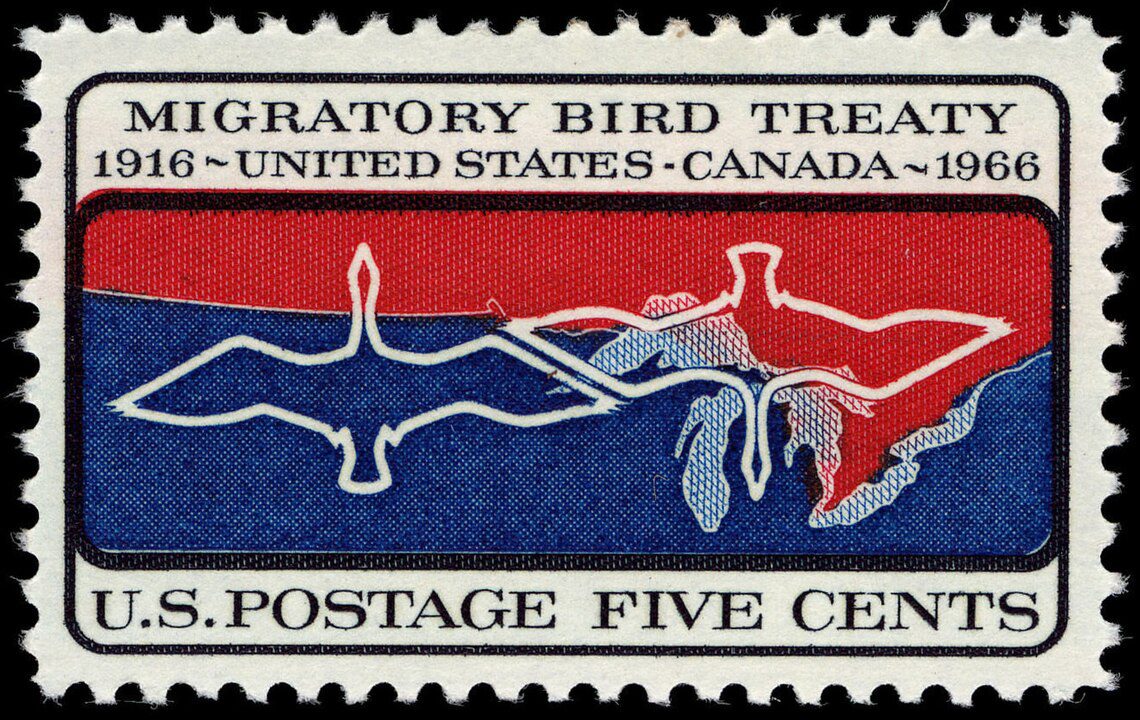

Since birds are flying large distances, it takes both national and international cooperation to ensure their safety. The loss of habitats due to pollution or exploitation is the largest threat to migratory birds. The loss of any of their stop sites could have a dramatic impact on survival. Power lines and wind turbines also serve as a threat to migratory birds. Some migratory birds, like ducks, geese, and cranes, are popular to hunt. It’s important to follow your region’s guidelines when hunting these animals. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) of 1918 is an international treaty that protects almost all species of migratory birds. This law strictly prohibits the killing, capturing, selling, or transportation of migratory birds and their eggs. It protects thousands of species.

The official stamp created by the U.S Postal Service in 1966 to commemorate the treaty. Designed by Burt E. Pringle.

Even if you’re not a hunter, supporting groups such as Ducks Unlimited or Delta Waterfowl can be an effective way to help these species. These groups fight to conserve wetlands, grasslands, and other habitats used by migratory waterfowl and birds. You can donate money or volunteer your time with local chapters.

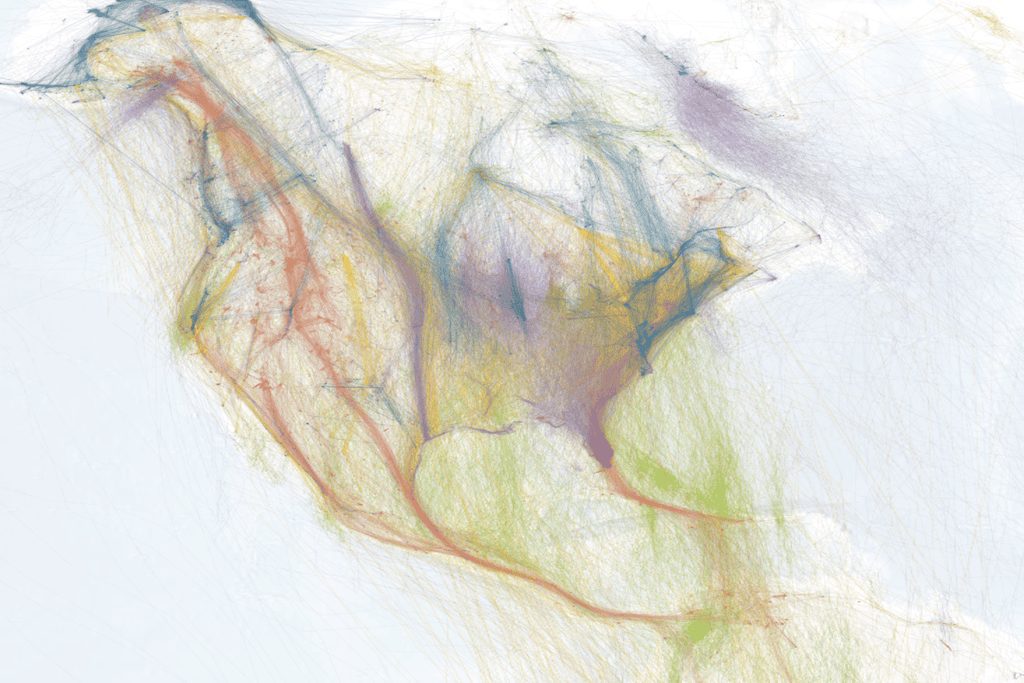

Many migratory bird species are tracked using tagging methods. Using a variety of different techniques, such as leg banding, scientists can closely monitor population sizes. They can also track where the birds are going and identify any significant changes. Audubon National Society has created a digital interactive map to track migratory bird species.

Bird Migration Explorer interactive map created by Audubon. Data supplied by researchers tracks over 12,000 individual birds annually. Each colorful line tracks the migratory journey of a variety of different species.

Every migratory bird that passes over Minnesota depends on habitats far and wide — wetlands in the north, forests in the Midwest, and wintering grounds in the south. Protecting these habitats isn’t just about the birds; it’s about preserving a chain of life that keeps ecosystems balanced, waters clean, and soils fertile. Our choices today — conserving wetlands, planting native species, reducing pesticide use — directly influence whether future generations will still see the sky come alive each fall.

In short, migration is a story of survival, adaptation, and interconnection. When we care about birds, we care about the health of the planet, our communities, and ourselves.

Here at Campfire Bay Resort, we get incredible viewing of many migratory species. Come stay with us in the fall, and get a wonderful show!