Minnesota’s Native Pollinators: A Dying Breed

The foremost pollinator in everyone’s minds is the bee. Usually, the honeybee. But honeybees are invasive, and are in fact native to Europe. While they are helpful, making space for them results in us losing our native pollinators. So let’s meet them and see what we can do to help them.

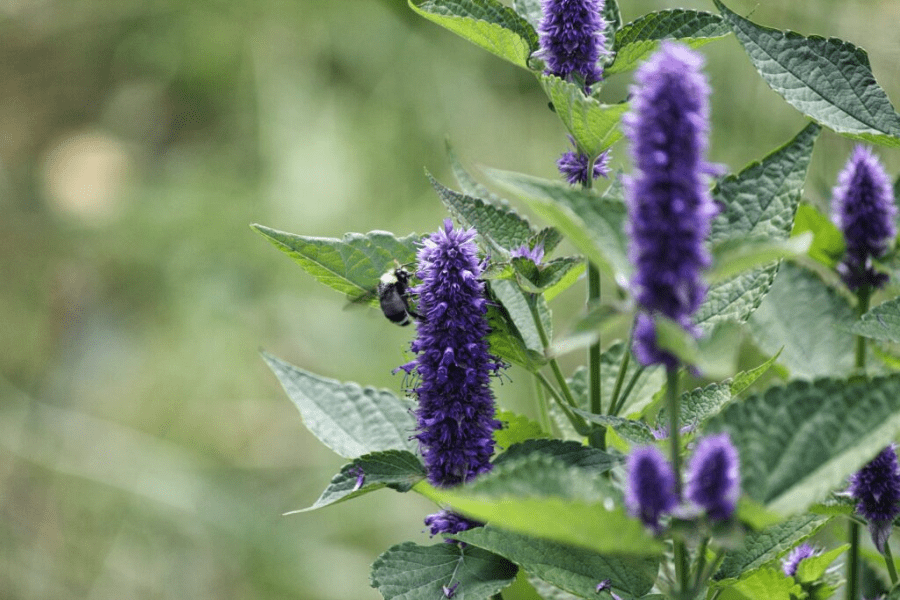

Imagine: you’re walking through a sparse patch of woods, on a barely-there trail. You can hear the bees and other bugs buzzing through the undergrowth. Flowers pop up here and there. Yarrow, milkweed, aster, anise hyssop, daisies and so forth. They provide not only color and intrigue to an already gorgeous landscape, but food to everything living in these woods. Something, loud and buzzing, flies past your ear. You don’t swipe–instead, you dodge to the side, and watch as a fat black-and-gold insect lazes through the air before landing on one of those flowers you were admiring a moment ago. Looking closer, you notice a small, rust-shaded patch atop its bum. You’ve spotted one of the rarest native pollinators in Minnesota: the Rusty Patched Bumblebee.

Once filling our farms, fields, and the edges of our forests, these little friends are now on a drastic decline thanks to pathogens from commercial bumble and honey bee colonies, as well as pesticides and habitat loss. But Minnesota’s state bee is not without friends and supporters. So today, we’re learning about the pollinators in our great state, as well as how we can help those that need it.

Minnesota’s Pollinators

Name five pollinators you can think of here in Minnesota. It’s okay, I’ll wait. Most people’s minds only go to butterflies and bees, which are only two out of the five I suggested, unless you go really in depth and begin naming their specific breeds. Okay, here are the five I have: bees, wasps, moths, butterflies, and hummingbirds. Seems obvious now, right?

Okay, one more question. I’d like you to name five invasive species of pollinators here in Minnesota. That’s a bit tough, now, isn’t it? Well, it’s okay, because the first thing we’re going to talk about are the invasive species here in Minnesota before discussing our native species, and how their interactions cause harm to the bugs that belong here.

European Honeybee

Invasive Pollinators

Most of the pollinators you’re thinking about are likely invasive. If I ask you specifically to think of bees, what comes to mind? A honeybee, perhaps. Or maybe a really big, fuzzy bumblebee with a white butt to disrupt the usual black and yellow pattern. What if I told you those two – the European Honeybee and the Buff-Tailed Bumblebee – are both invasive?

Now, when I say invasive, you likely think of something similar to Zebra Mussels, which choke out the micro-organisms in our lakes and disrupt the food web (among other things). And honestly… that’s accurate. While they aren’t as parasitic and fast-populating as the Zebra Mussel, honeybees and the Buff-Tailed Bumblebee are not native here. They are not a natural part of the food web and therefore tend to out-compete our local pollinators for resources and habitat.

What Invasive Pollinators Do

Most of the things threatening pollinators – habitat loss, diseases, and parasites in particular – are worsened or caused by these invasive pollinators.

Habitat loss, while largely the fault of corporations looking to expand into grasslands, more neighborhoods that don’t need to built, and large-scale agricultural practices that focus on a monoculture across a huge swath of land, isn’t helped by honeybees and bumblebees beating them out for competition of flowering plants.

Diseases and parasites, however, are largely the fault of commercial honeybee operations, and in general the species themselves. Foulbrood (both the American and European strains) and Chalkbrood are the most common diseases to be spread from honeybees to other pollinators – especially our locals. Nosema is a parasite often spread from honeybees to other species as well, causing dysentery and other symptoms.

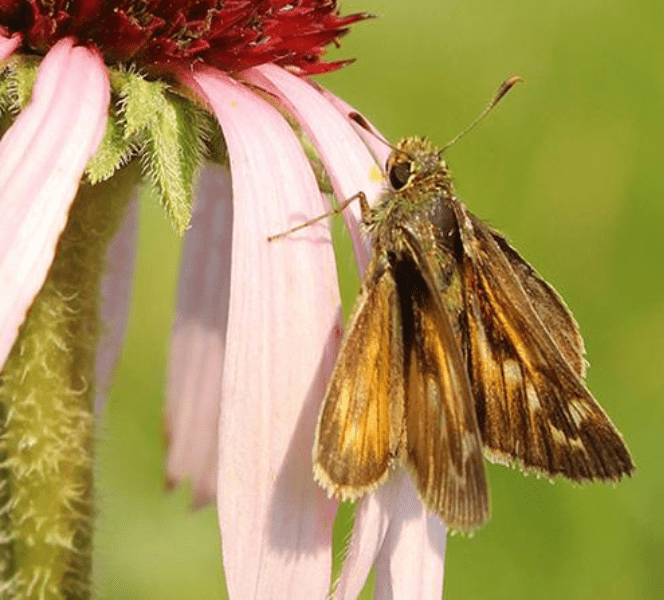

Dakota Skipper

Native Pollinators

North America – and Minnesota in particular – has so many amazing native pollinators. From butterflies to hummingbirds and beyond, there are so many beautiful little creatures who help our ecosystem thrive. Two I want to talk about today are the ones that are currently suffering the steepest decline in population and health.

The first is a butterfly known as the Dakota Skipper. Entirely reliant on its native prairie habitats, their decline is thanks to large scale agriculture and building developments. So far, few to no attempts at recreation of their habitats, burns, and so forth have been able to revive their dwindling population. Their range has been cut to only a few counties in western Minnesota, and the only things keeping them alive are government owned native grasslands and pollinator gardens owned by private homeowners.

Next to them in decline is Minnesota’s state bee: the Rusty Patch.

The Rusty Patch Bumblebee

The Rusty Patch Bumblebee

The Rusty Patch Bumblebee is a bee that is native to the midwest and northeastern United States. Sharing a similar range with Sugar Maples, these little guys are one of the many beautiful native bees to Minnesota.

And, sadly, the one facing the most dangers.

With habitat loss, diseases and parasites spread by non-native bees, pesticides that poison and kill not only the food and plants they need to survive, but the bees themselves, and the temperature shifts caused by climate change, our little bumblebee was placed on the critically endangered species list over a decade ago, in 2014. It’s even more of a concern due to the fact that it’s not just the workers that forage, but everyone in the hive – including the queen. This means that all bees in a colony are at risk out and about, not just in their hives.

Now, the question that’s bound to pop into some peoples minds is “why do we care?” And to an extent I do understand why this question comes up – we do have a ton of other pollinators. Their loss won’t devastate the honey industry in the US. After all, they’re a wild bee. But I ask you this in return: why do you think we shouldn’t?

The loss of this bee means the loss of a crucial creature in the food web and the broader ecosystem. Yes, we have honeybees and bumblebees, but they do not fit the niche the same way the Rusty Patch does. Too often people are obsessed with bringing back species we’ve lost instead of keeping the ones we have. So, here are some ways you, as an average citizen, can help!

Pollinator Garden

How to Help our Native Pollinators

- Plant diverse flowering plants for the spring, summer, and fall. The biggest way to help is to increase the amount of foraging space they have! Both native and heirloom plants are welcome. The more that flower throughout the year, the better!

- Flowers to Plant: Aster, Bee Balm, Salvia, Anise Hyssop, Clover, Yarrow, Sunflowers

- Shrubs to Plant: Ninebark, Pussy Willow

- Provide habitat. It’s a struggle due to neighborhood developments for bumblebees to find shelter, since they often nest and overwinter in leaf litter, rotten logs, compost piles, brush, rock piles, and more. These are often considered “eyesores” to your local Homeowners Association, and the meticulous cleaning and pruning has taken their homes. Allow a leaf pile in the corner of your place, maybe near the garden, to offer shelter. Here at Campfire Bay Resort, we do our best to provide habitats for our local insects by leaving sections of our resort unmowed for the purpose of nesting. We also regularly plant flowers and other flowering plants around the resort. They’re not just pretty, they help keep our ecosystem running smoothly!

- Keep pesticides away from areas they nest and forage. Most forms of pesticides don’t just poison the crop for them – it will outright kill a bee that comes into contact with it. If you’re very concerned, consider netting your plants or looking at natural ways to keep pests out of your garden.

Thank you for taking the time today to learn about our native pollinators and what you can do to help them! We only have one earth, so let’s do our part to keep it and all who call it home healthy.